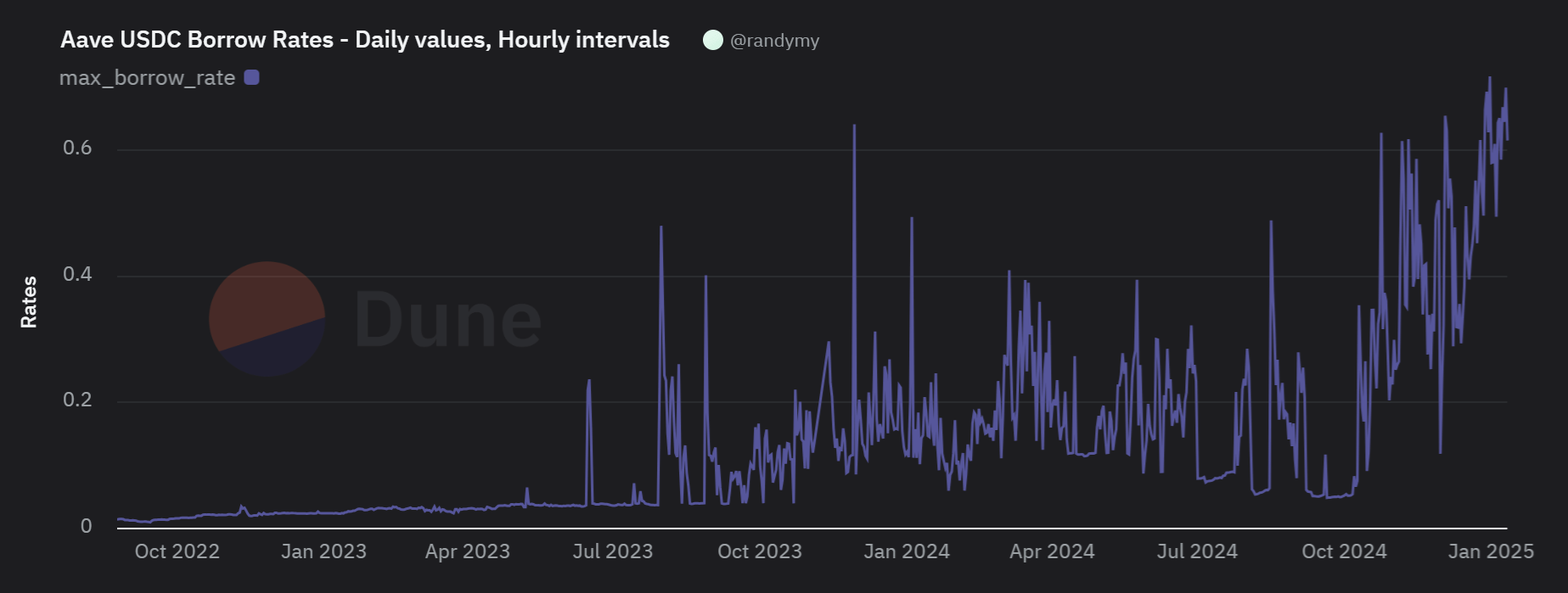

1. High Stablecoin Borrowing Rates

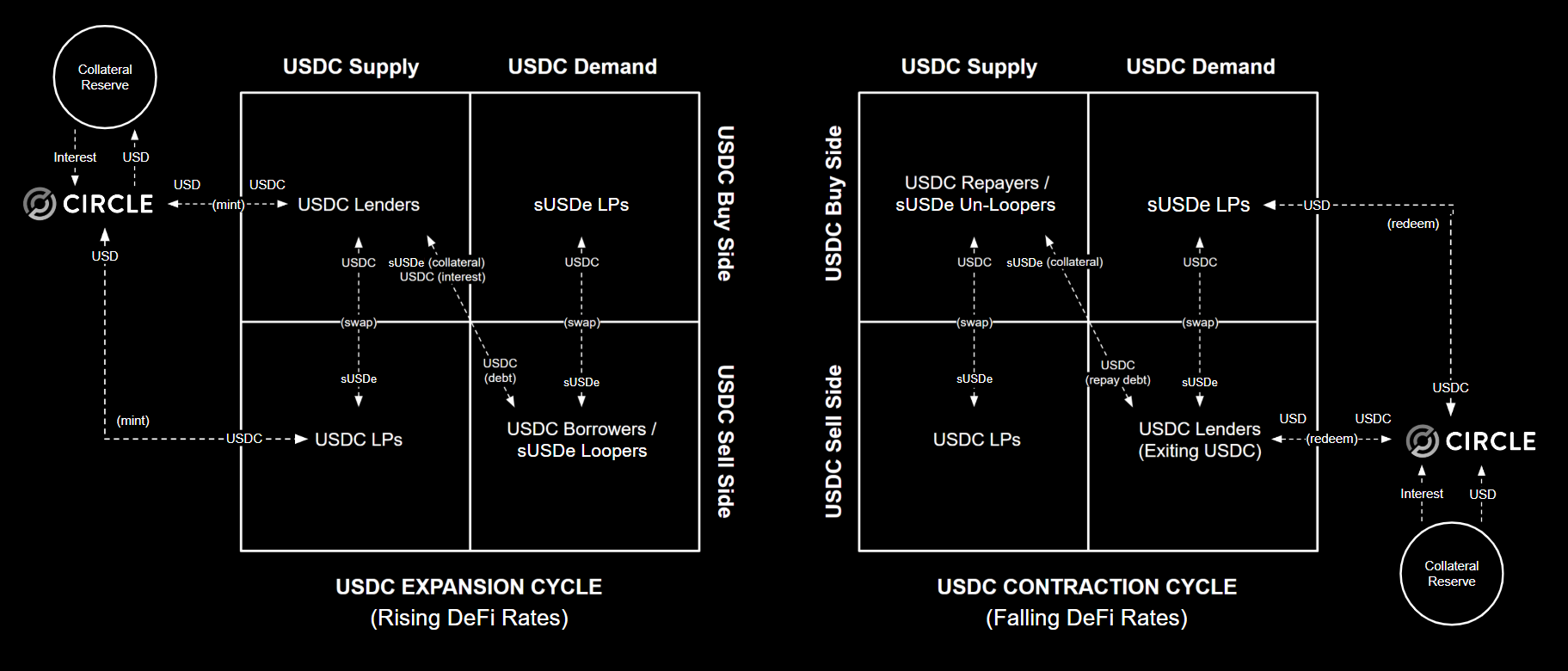

Elevated Fed interest rates and growing demand for on-chain credit have driven up borrowing costs for digital assets in recent years, particularly for stablecoins—which now comprise nearly half of DeFi's total outstanding debt. This creates an ongoing challenge for stablecoin borrowers who face rising interest expenses as the demand for on-chain credit continues to grow.

2. No Benefits from Major Stablecoin Reserves

The leading stablecoins, USDT and USDC, generate substantial interest earnings from their collateral reserves. However, these profits don't benefit end users directly. Instead, issuers like Tether and Circle internalize most of these earnings, creating a disparity in value distribution.

As of Q2 ‘25, over 95% of stablecoin reserves globally are allocated in RWA, such as bank deposits, money market instruments, and short-dated government bonds—yielding above 4% APY. In theory, these yield streams from TradFi could be redirected to stablecoin users and dApps to stimulate on-chain economic activities. By externalizing reserve earnings, the stablecoin industry could evolve from a centralized profit center to a key driver of growth in decentralized economies, aligning more closely with DeFi's core tenets of financial inclusivity and user empowerment.

3. Structural Drawback for Yield-Bearing Token Borrowers

Liquid-staked tokens (LSTs) and liquid-staked stablecoins (yieldcoins)—such as sUSDS, sUSDe, sfrxUSD, sfrxETH, stETH, etc.—are yield-bearing, supply-side assets designed to externalize earnings to their token holders, including users who supply them to DeFi protocols. On the other hand, demand-side users who borrow yieldcoins face a significant drawback: rapidly growing debt due to the token’s intrinsic yield, which compounds as additional debt on top of borrowing costs.

To date, no LST and yieldcoin project has addressed the structural issue of yield-to-debt accrual for borrowers (other than dTRINITY), making them less attractive than vanilla token and stablecoin loans. While they remain popular among holders and suppliers who typically pledge them as collateral to borrow non-yielding tokens, users generally avoid borrowing yield-bearing tokens. As a result, these assets have very low utilization rates on lending protocols (i.e., high capital inefficiency). This creates a structural imbalance in DeFi where LST and stablecoin yield distributions disproportionately benefit the supply side, leaving borrowers on the demand side at a disadvantage.